June 2022

Fig.1

Edison Opera cylinder phonograph, type SM, model A, Thomas A. Edison, United States, 1912, inv. 4279

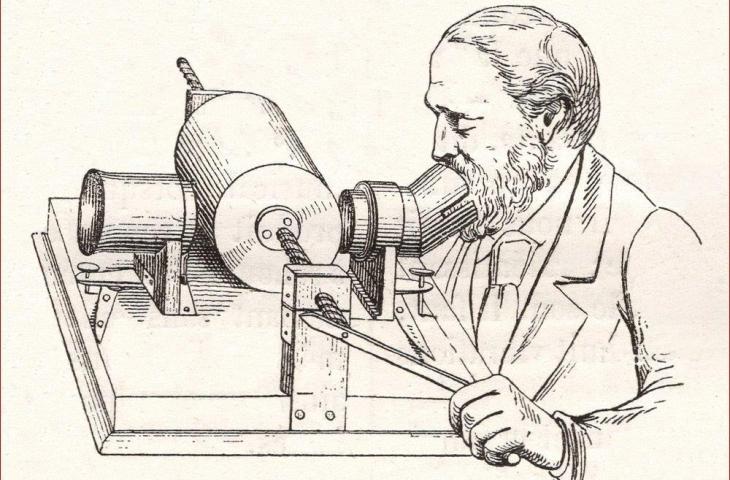

Fig.2

Edison and his phonograph, Levin Handy, 1878, Washington D.C., © M.B. Brady

Fig.3

Thomas Edison's assistant Charles Batchelor recording his voice, 1878, © The Daily Graphic

Fig.4

Blue Amberol cylinders

On 19 December 1877, the American inventor Thomas Edison patented the phonograph, a device that allows 2 minutes of sound to be recorded and played back on a tin cylinder. A crank turns a cylinder covered with tin foil. You then have to speak into a conical tube with a stylus at the other end. The compressed air in the tube causes the stylus to vibrate, etching grooves in the cylinder material caused by these movements. To listen to the recording again, the process is reversed. The voice recorded a few minutes earlier resounds again in the room. The talking machine was born.

This invention was so singular, so strange, so unexpected, that it initially aroused general disbelief. Edison was branded a wizard! In England, when the first phonograph imported from America was presented, there was a bishop in the audience, John H. Vincent, who, suspecting some trickery, wanted to put the machine to the test. In front of the recorder, he lists a number of proper names from the Bible at high speed. The machine then repeats them correctly and the prelate confesses: "Only I in the whole country can recite these names so quickly!"

At first, the machine was mainly used to record voices for educational purposes (lessons, books, etc.), for entertainment (talking toys), advertising or public announcements. The possibility of musical reproduction was only incidentally considered, far from imagining the extraordinary future of the phonograph in this field. It must be said that at the time, having a machine at home that played "recorded" music was a completely incongruous idea. Moreover, the use of tin created a lot of "metallic" sound parasites due to the rubbing of the stylus and its wear and tear often allowed only one listening. In 1887, Edison took up the idea of competitors by replacing tin with wax, which was more efficient.

The wax cylinder phonograph became popular, even if its role as a musical reproducer was still secondary, as testified by this sales catalogue from a Paris house at the end of the 19th century : "We are no longer in the days when the phonograph was classed as a scientific hoax. No one doubts today that speech can be stored, that it can be talked about indefinitely, and that it can be produced at will, all of which is achieved by the phonograph. [...] The 'Wizard of Menlo-Park', as he is called in America [after the site of Edison's laboratories in New Jersey], has introduced such improvements into his invention that the phonograph will no longer be an object of curiosity, but an instrument that is both pleasant and has a marked place in the home".

This in no way detracts from the mocking tone of some, such as Paul Morand in his book "1900": "The phonograph! At last! The latest triumph of science - a simple roll and Coquelin [a famous actor on the Parisian stage] says a monologue in your bedroom. Larynx and vocal cords of wax. Thorax of nickel... Everyone now knows this fantastic machine that speaks, sings, laughs and sobs, this machine capable of preserving forever the joyful cries of the baby and the words of the grandfather who is going to sleep for eternity."

Nevertheless, music eventually took hold of the device and, in no time, the phonograph industry boomed at the turn of the century. Along with flat disc gramophones, companies flourished everywhere and producers relied on an eclectic repertoire as soon as they entered the industrial production phase. The advent of cylinder casting allowed companies to free up time and budgets to expand the recorded repertoire. They thus diversified their potential audience, which was essentially made up of the small and middle classes in search of new cultural practices.

Edison's Opera model marked the heyday of cylinder phonographs [fig. 3]. Produced from 1911 to 1913, this luxury phonograph was specifically designed to take full advantage of Edison's more robust Blue Amberol hardened celluloid cylinders, which could play for up to 4 minutes and 45 seconds [fig. 4]. The sound qualities of the Edison Opera are excellent, not least because it has a new system in which the cylinders move under the needle rather than the other way round. Contrary to the usual practice, the pickup and the bell remain fixed and it is the cylinder that moves forward during the audition while rotating on itself [video]. Thanks to this complex technical feat, the horn can be much larger than in most other instruments. The Edison Opera is said to have probably the best sound of all contemporary instruments, both cylinders and records. It is capable of producing enough volume to fill an average concert hall of the time, hence the name. This model also has an automatic stop device that can be set on the last groove of a cylinder and then forces the machine to stop. The heavy-duty spring motor is capable of playing up to a dozen cylinders per winding. In 1913, the Opera was renamed the Edison Concert Phonograph.

Nevertheless, despite the undeniable sound qualities of the phonograph, consumers increasingly disdained cylinders, preferring the flat discs of gramophones, which were easier to store and less fragile. Many cylinder manufacturers went out of business and Thomas Edison remained the last defender of his invention against all odds, finally abandoning the production of cylinder phonographs in 1929.

Text: Matthieu Thonon