July 2024

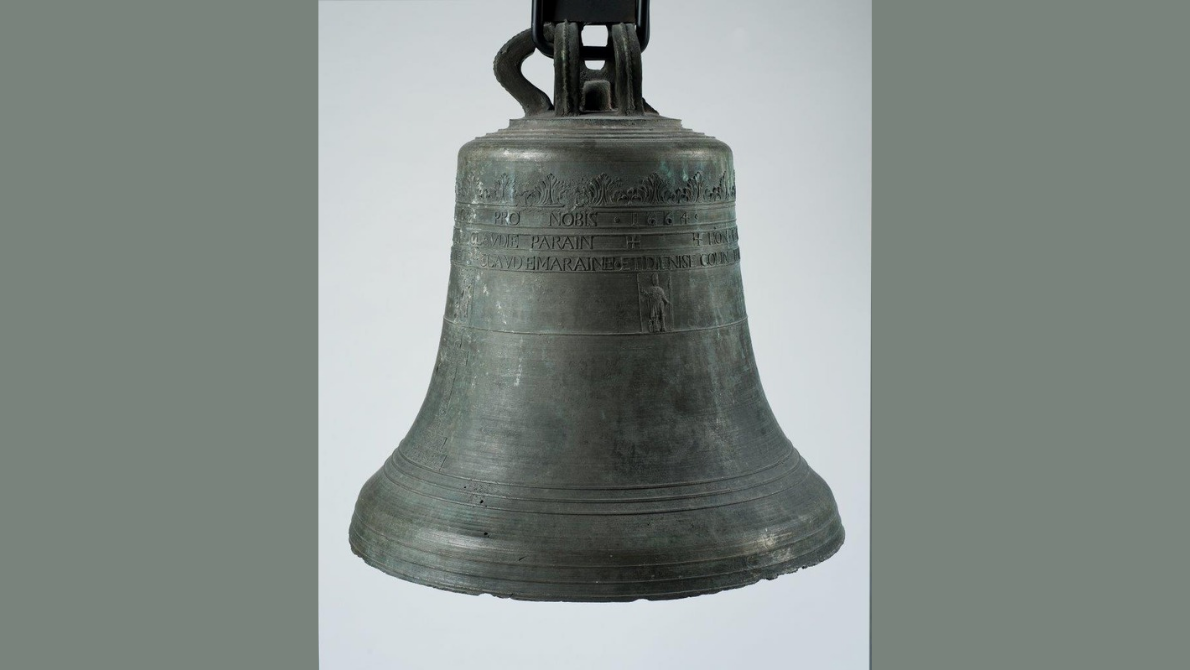

For more than three centuries, this bell was the soul of Avignon-lès-Saint-Claude, a small village in the Jura Mountains (Eastern France). With its ringing it watched over the surrounding woods and fields. It was cast in 1664, and it hung in the tower of a chapel that had been erected some years before, in 1649, in gratitude after the village had escaped the plague epidemic that had hit the area in 1629 and 1636. The chapel was devoted to Saint Roch, the patron saint against the plague. The inscription STE ROCHAE ORA PRO NOBIS on the bell bears testimony to this. The body bears different images: a big crucifix adorned with vegetal garlands, a baroque calvary crowned with the sun and the moon, effigies of the Virgin Mary, of Saint Roch himself with his dog, and of a blessing bishop with a child at his feet. This is Saint Claudius, who was reputed to revive stillborn babies for the time of their baptism. In 1975, as the bell was cracked, it was replaced by a new one, after which it was donated to the MIM.

This bell was made by Michel Jolly, a bell-founder from the village of Breuvannes-en-Bassigny, who would be succeeded by his four sons. The Bassigny is an area in the neighbourhood of Langres. In those times it was a hotbed of highly reputed wandering bell-founders. From the 16th century onwards they travelled all over eastern France and the neighbouring Swiss cantons from spring to autumn. They set up their workshops wherever their services were required. The first permanent workshops only arose late in the 19th century. Until then, bells were cast on the spot, in front of, and sometimes even inside the church. Two casting moulds are still to be seen in the basement of the nearby church of Saint Lupicin.

The casting of a bell was an important occasion in the life of a village community. The extant contracts of parishes with bell-founders often show the enthusiasm the event sparked off, and they also provide surprising details about the bulk of the materials the client had to provide: up to 30 cartloads of stone and clay to make the mould and the oven, and up to thirty cartloads of coal and firewood. Workers had to be hired to mould the clay and cleave the wood, and to hang the finished bell in the tower. The bell-founder could count on the passionate help of the local community around him.

When the mould was ready, it was buried in a hole and carefully covered with earth. Then the bell-metal – an alloy containing around 80% copper and 20% tin – was heated to 1200° C. Every maker had his own ‘secret’ recipe, which added to the mystery around bell founding. When the metal was liquid, the trapdoor of the oven was opened. Through a channel the metal slid into the mould like a fire snake, and disappeared into the earth. The whole process only took a few moments. In the old times the bell makers liked to wait until night had fallen. Then the scene looked even more magical and spectacular in the eyes of the excited villagers who had gathered to experience the ‘miracle’.

Once the cast was taken from the mould, it was washed and consecrated, or ‘baptized’ in popular speech, as it was given godparents and a Christian name. This bell was baptized Marie-Joseph, and F. IAILLO and DENISE COLIN were named as godparents. We don’t know exactly who they were. However, both surnames were well attested in the village at the time. ‘F. Iaillo’ undoubtedly points at a member of the Jaillot family, which produced two brothers who made a career at the court of Louis XIV: Hubert (1640-1712), a prominent geographer, and Pierre Simon (1631-1681), a famous ivory sculptor. Some other Jaillots from Avignon-lès-Saint-Claude were also successful in Paris. In a village of barely 120 souls at the time, all these Jaillots must have been relatives of the godfather of our bell. Further investigation could clarify this,

Text: Stéphane Colin