February 2023

Fig.1

Kemângeh roumy, Egypt, 1701-1800, inv. 0225

Fig.2

François-Joseph Fétis (1784-1871)

Fig.3

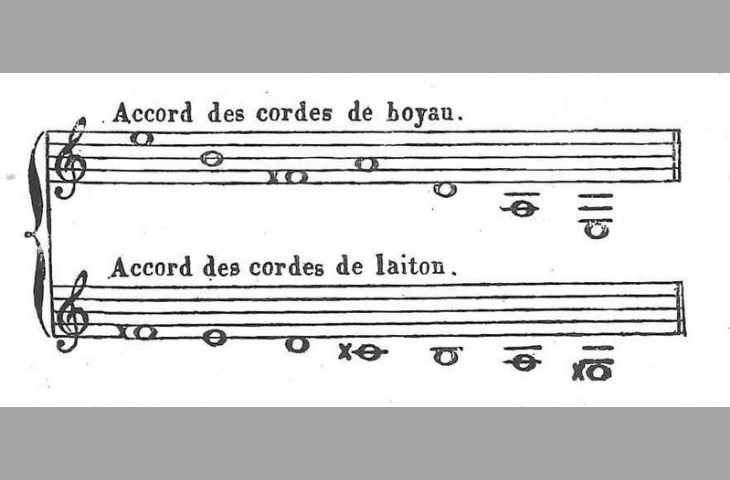

Tuning of the kemângeh roumy, François-Joseph Fétis, Paris, 1869

Fig.4

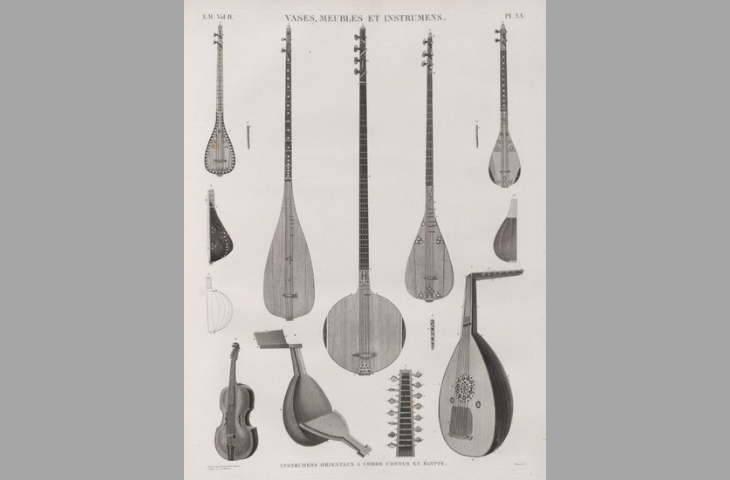

Plate AA of Villoteau (in Description de l’Égypte. Planches, 1817), n° 14: Kemangeh roumy

An acquisition by Fétis in Egypt

When in 1878 Victor Mahillon (1841–1924), the first curator of the Musée des instruments du Conservatoire in Brussels, inventoried the nearly 300 instruments then making up the new museum’s collection, he categorized this instrument as a German viola d’amore. From a purely formal point of view, this was not an illogical decision. Its morphology is that of a viola d’amore, a bowed chordophone with sympathetic strings, which enjoyed a certain success in the eighteenth century, especially in German-speaking countries and in Italy.

However, we now know that instrument inv. no. 0225 (fig.1) comes from Egypt. With the help of the Belgian government, François-Joseph Fétis (1784–1871) (fig.2), director of the Brussels Conservatory and Kapellmeister to Leopold I, acquired in 1839 a collection of sixteen Arabic instruments through Étienne Zizinia (or Stephanos Tsitsinias, 1794–1868), a wealthy Greek shipping magnate, naturalized French, and newly appointed Belgian consul in Alexandria.

Among the sixteen instruments which Zizinia collected for Fétis in Alexandria - lutes, flutes, oboes, drums, lyres, zithers and viols - was this ‘kemangeh roumy’. As noted, the instrument exhibits characteristics of the European viola d’amore: it has seven melodic strings and seven sympathetic strings, which run under the fretless fingerboard (fig.3). The flame-shaped sound holes are typical of the viola d’amore. The black varnish covering the instrument is also a recurring feature of bowed instruments built in Austria in the second half of the eighteenth century.

According to Fétis, one particularity that distinguishes the kemangeh roumy from the European viola d’amore is its tuning, which is reversed compared to Western bowed instruments. However, an internal examination indicates that the kemangeh roumy was made either by a European violin maker or someone trained in European techniques. Why then did Fétis place a retuned European viola d’amore on his "Egyptian" wish list?

Between eastern use and western craftsmanship

Forty years before Fétis, Guillaume André Villoteau (1759–1839), one of the savants who joined Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign (1799–1801), had illustrated a similar kemangeh roumy in the famous Description de l’Égypte (fig.4). Fétis was well aware of Villoteau’s publication. He likely aspired to build a comparable Egyptian collection, which may explain why he included a kemangeh roumy in the list sent to Zizinia.

The testimonies of Villoteau and Fétis raise the question: was the European viola d’amore actually used by local musicians in late eighteenth-century Egypt? It is known that in the second half of the eighteenth century, violas d’amore were among the goods traded between Europe and the Ottoman Empire - of which Egypt was a part, despite some Mamluk ambitions for autonomy. The earliest reports of violas d’amore being played in Istanbul appear in the 1760s. In his Mémoire sur les Turcs et les Tartares, Baron de Tott (1733–1793) describes a concert performed by a Turkish chamber orchestra, featuring a viola d’amore called sine keman in Turkish (literally, "chest fiddle"). The sine keman became a favourite at the imperial court in Istanbul, eventually replacing the kemançe, a Persian spike fiddle.

A singular instrument’s journey

In Egypt, the viola d’amore was referred to as a roumy viol or "Greek violin", pointing to its foreign and non-Muslim origins. When Villoteau saw kemangeh roumys in Cairo at the end of the 1790s, he described and depicted one in his report, but deemed it not interesting enough to bring one back to France. Apart from Villoteau’s drawing and Fétis’ instrument, no other examples of Egyptian kemangeh roumys in the form of a viola d’amore are known. Fétis’ kemangeh roumy is therefore possibly the first (and only?) such instrument brought to Europe. It was likely Austrian in origin, and may have travelled from Vienna to Alexandria and then on to Brussels.

After Fétis’ death in 1871, his sons Édouard and Adolphe sold his instrument collection to the Belgian State. In 1873, the instruments were housed in the library of the Conservatoire royal de musique. In 1877, the collection - including the kemangeh roumy - was incorporated into the new Musée instrumental of the Conservatoire.

Text: Saskia Willaert, Fañch Thoraval, Anne-Emmanuelle Ceulemans

Full research