October 2023

Fig.1

Oud, unknown builder, Egypt, inv. 0164

Fig.2

Oud, unknown builder, Egypt, inv. 0164

Fig.3

Oud, unknown builder, Egypt, inv. 0164

Fig.4

François-Joseph Fétis, 1860, Photo: Ghémar Frères

Fig.5

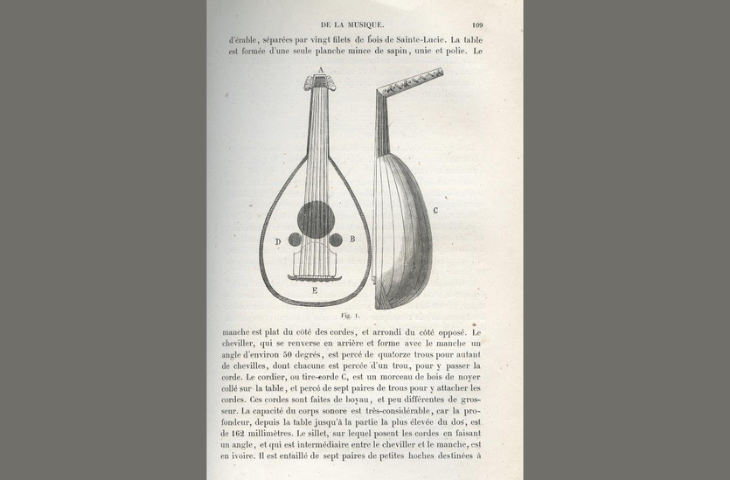

Extract from Histoire de la musique, François-Joseph Fétis, Brussels, 1869, vol. 2

Fig.6

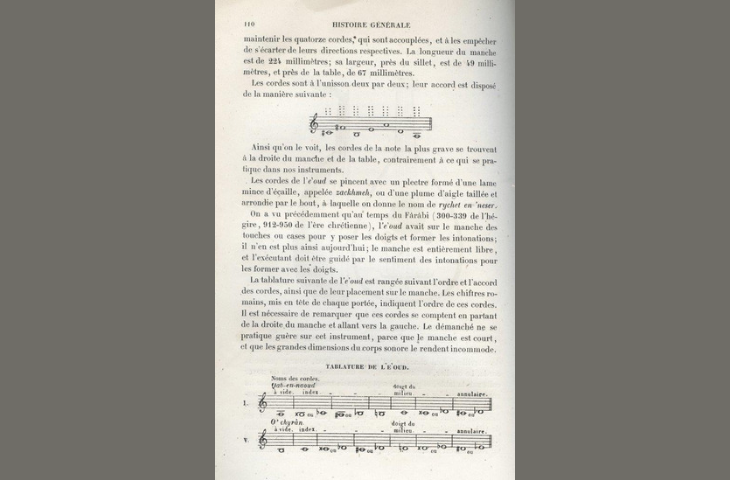

Extract from Histoire de la musique, François-Joseph Fétis, Brussels, 1869, vol. 2

Fig.7

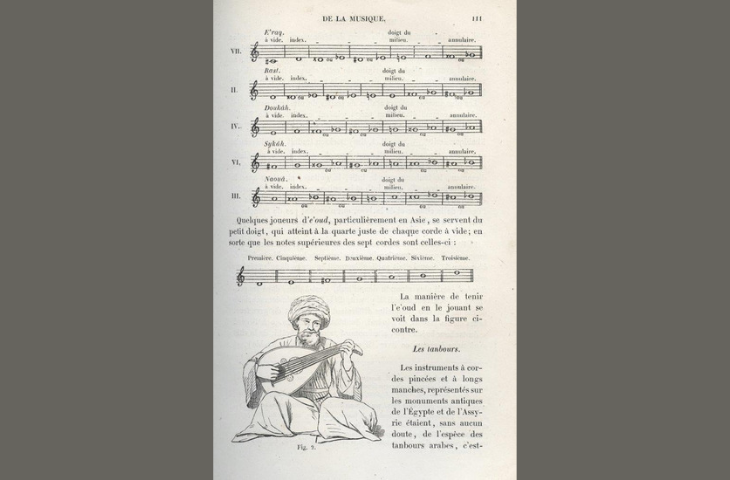

Extract from Histoire de la musique, François-Joseph Fétis, Brussels, 1869, vol. 2

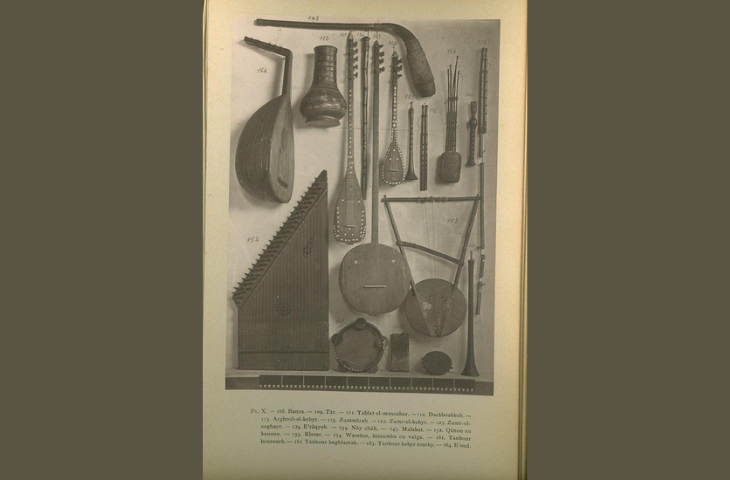

Fig.8

Extract from Album des instruments extra-européens du Musée du Conservatoire royal de musique de Bruxelles, Victor-Charles Mahillon, 1878, plate X

The oud: an ancient plucked instrument

The oud is a plucked instrument with a pear-shaped soundbox built around a mould, and a short, angled back neck. The gut strings are plucked with a plectrum made from a piece of tortoise shell or an eagle feather.

The oud plays a prominent role in Arab music; it is called the ‘sultan’ of Arab instruments. The name ‘oud’ is derived from the Arabic العود al-ʿūd (‘twig’, ‘piece of wood’). Over its long history, the instrument travelled from East to West - from Baghdad (7th century), via Asia Minor and the Arabian Peninsula, to Northeast Africa and Andalusia (9th century). It is the immediate precursor of the Western lute. Both instruments are very similar, but the oud has no frets and its neck is narrower.

The oud forms part of the classical Arab orchestra, but also plays solo and in small ensembles. It is heard in traditional and contemporary repertoires, including ethno-jazz, Mediterranean folk, world fusion, sufi, qawwali, and new-age music.

Virtuosos and the spread of the oud

Many outstanding oud virtuosos played a key role in promoting and spreading the oud. Scharif Muhyi ad-Din Haydar Targan (1892–1967), a Turkish musicologist, founded the first school for oud concert soloists at the Baghdad Conservatory in 1934. One of his students was the Iraqi Munir Bashir (1930–1997), who became one of the most acclaimed oud players worldwide; he was called the ‘Ravi Shankar of the oud’ and promoted the instrument during concert tours in Europe and the U.S. Riad Al Sunbati (1906–1981) from Egypt was an excellent oud virtuoso who composed numerous songs for Oum Kalthoum. Saïd Chraïbi (1951–2016), a Moroccan composer and internationally acclaimed oud player, applied technical innovations to the instrument and built sopranino, soprano, and bass ouds. Nasser Shamma (Iraq, b. 1963) studied at the Baghdad Conservatory and founded his own schools in Cairo and Tunis. He trained the first female oud concert performer, Youssra Dhahbi (b. 1966), called the ‘princess of the oud.’

Other internationally acclaimed contemporary oud players include Rabih Abou-Khalil (Lebanon), Simon Shaneen (Palestine-Israel-U.S.), Anouar Brahem (Tunisia), Dhafer Youssef (Tunisia), and the Joubran brothers (Palestine). In Belgium, the ensemble Luthomania promotes ensemble playing of oud, lute, and Chinese pipa.

The MIM’s oud No. 0164: a historical testimony

The oud with inventory number 0164 at the MIM is the oldest known oud preserved in a public collection. It has seven double strings, typical of the 19th-century Egyptian oud. The instrument arrived in Brussels from Alexandria in 1839, thanks to the Belgian musicographer and then director of the Brussels Conservatoire Royal de Musique, François-Joseph Fétis (1784–1871). With the help of Étienne Zizinia, the Belgian consul in Alexandria, Fétis acquired sixteen Arab instruments for his personal collection—a purchase for which he reportedly made great financial sacrifices. Incidentally, he only settled the bill in 1846.

Besides the oud, Fétis’s collection from Alexandria contained a qanun (zither), a kissar (lyre), tanbur lutes, a nay (flute), a zamr (oboe), an arghul, and kemanche (fiddles). Fétis claimed he had assembled ‘the most comprehensive collection of such instruments in all of Europe.’ This is not entirely accurate: nearly forty years earlier Guillaume-André Villoteau (1759–1839), a scientific member of Napoleon’s expedition in Egypt (1798–1803), had brought a similar collection to Paris, representing the different communities living together in the major Egyptian cities (Arabs, Nubians, Copts, Ethiopians, Persians). That collection counted at least 22 instruments. Unfortunately, Villoteau’s oud has not been preserved. Fétis knew Villoteau personally; correspondence between them survives. Fétis was well-informed about Villoteau’s work and was undoubtedly inspired by Villoteau’s collection when assembling his own Egyptian collection.

Further information on the circumstances in which Fétis acquired these sixteen Egyptian instruments can be found in the article on the Kemangeh roumy.

Fétis and 19th-century Arab music

In the 1830s, Fétis developed the ambition to write a comprehensive Histoire de la musique, covering not only Western music but the whole world, including Arab music. For him, the history of music was ‘inseparable from the appreciation of the special abilities of the races that cultivated it.’ Just like language, every race had its own music. His discourse is heavily imbued with categorization, stereotyping, Eurocentrism, and paternalism typical of the 19th century. Western music, he wrote, ‘is the only true art; but it remains interesting to know the primitive forms of that same art.’

He gave an elaborate theoretical description of Arab music and musical instruments. He claimed the tonal systems of Arab peoples were ‘incompatible’ with our musical sensibility, mainly because each tone is divided into three microtones, not two semitones like in our scales. His study of Arab tonal systems was based on translated Arab treatises, Villoteau’s work, and his own observations of the tuning and compass of the instruments in his collection - but not on the music as it was heard. It is doubtful that Fétis heard much Arab music. The very first concert of Arab music in Europe likely took place during the 1867 Exposition universelle in Paris, when five musicians performed at the ‘Café Tunisien’. The oud played the melody in unison with the rebab, accompanied by a tambourine and darabouka. After attending, Fétis wrote: ‘I have heard the musicians from Tunis, and I found their intonations false and their songs monotonous.’

After Fétis’s death in 1871, his sons Édouard and Adolphe sold all his musical instruments to the Belgian State. In 1873, they were housed in the library of the Conservatoire Royal de Musique. At the opening of the Musée instrumental in 1877, the Fétis collection of nearly one hundred pieces comprised almost half the museum’s collection.

Text: Saskia Willaert