March 2022

Fig.1

Harp, Cousineau père et fils, 1780-85, inv. 0246

Fig.2

Signature of the maker, inv. 0246

Fig.3

Scroll detail, inv. 0246

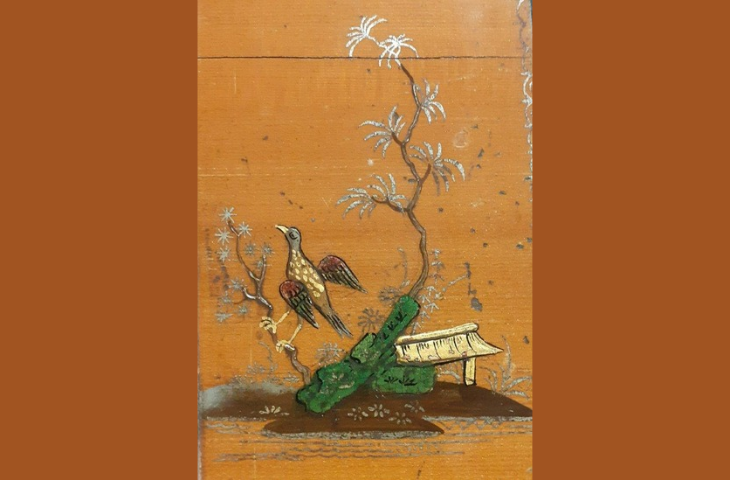

Fig.4

Decorative detail, inv. 0246

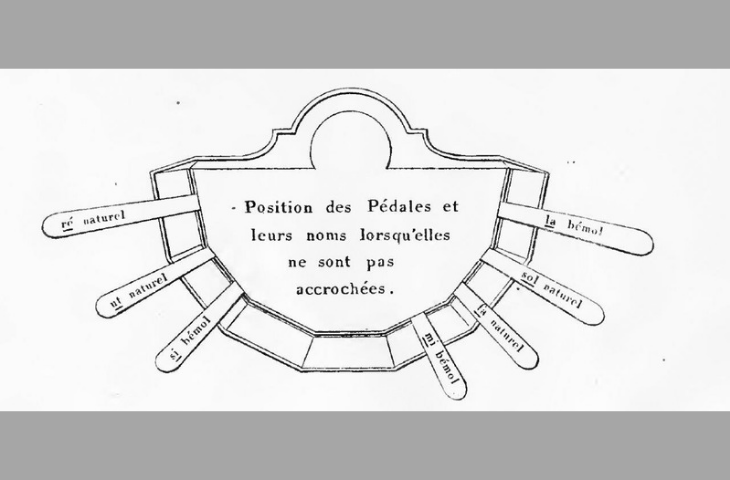

Fig.5

Jacques-Georges Cousineau, Méthode de harpe, Paris, s.d., p. 10

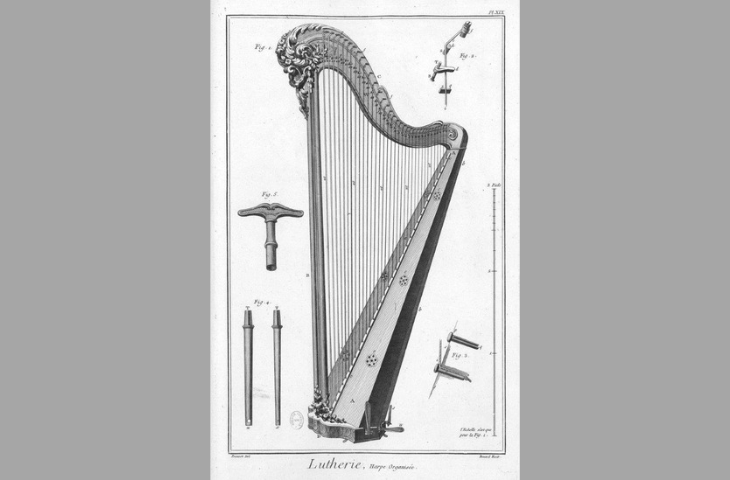

Fig.6

Diderot and d’Alembert, Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers : Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux et les arts méchaniques, Paris, 1767

Fig.7

'Béquille' system, inv. 0246

An exceptional Parisian harp

The Cousineau pedal harp inv. 0246 (fig.1) is one of the first instruments acquired by Victor-Charles Mahillon (1841–1924), the first curator of the Musée instrumental du Conservatoire (now MIM), which opened in 1877. The instrument bears the inscription "Cousineau père et fils luthiers de la reine", painted in a speech scroll on the soundboard (fig.2). The harp was probably built around 1780–1785. The serial number “no 17 R” appears in several places on the instrument, which stands out for its refined decoration. The head's scroll is richly adorned, and the soundboard features delicate chinoiserie (fig.3–4).

Georges Cousineau (1732–1800) and his son Jacques-Georges Cousineau (1760–1836) were harp makers based in Paris. They worked for Queen Marie-Antoinette (1755–1793), among others. Jacques-Georges was himself a harpist and published a harp method in the early 19th century.

A technical challenge: achieving chromaticism

Cousineau father and son are known for several major improvements to the harp. Since the Renaissance, one of the main challenges of the instrument was access to chromatic tones. Most harps have seven strings per octave, one for each scale degree (C–D–E–F–G–A–B). An invention dating from the early 18th century allowed the strings to be shortened by a semitone using seven pedals located at the base of the instrument, making it possible to play three flats (B-flat, E-flat, A-flat) and four sharps (F-sharp, C-sharp, G-sharp, D-sharp). This system is illustrated in Cousineau’s treatise: four pedals are placed on the left side of the base and three on the right (fig.5).

When all pedals are released, the instrument sounds in E-flat major. When a pedal is pressed or “engaged,” the strings corresponding to the indicated degree are raised by a semitone. For example, pressing the E pedal shortens the vibrating length of all E-flat strings to produce E-natural. The instrument then sounds in B-flat major. This so-called “single-action” system does not allow playing in all major and minor keys, but it offers possibilities that were unknown on earlier harps.

Cousineau's mechanical innovation

To shorten the strings by a semitone, the pedals were connected to a mechanical device placed on the instrument’s neck. This was done through a rod mechanism inside the pillar. This is where Georges Cousineau introduced a significant innovation. Before him, the system in common use involved crochets (French for 'hooks') that shortened the vibrating length of the strings, as illustrated in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (fig.6).

With this “hook system,” the shortened strings were no longer aligned with the others - an important drawback that hindered fluid playing. Cousineau therefore devised a system known as the système à béquilles, in which depressing a pedal caused two metal levers (béquilles) to rotate—one clockwise and the other counterclockwise - to gently grip the string without pulling it out of line (fig.7).

This system was clearly a success, but it still had its weaknesses. The gut strings wore out quickly under the action of the béquilles and had to be replaced regularly. The patent for the double-action harp, filed by Sébastien Erard (1752–1831) in 1810, overcame this problem while allowing access to all major and minor keys. The double-action harp eventually became the standard and is still used in orchestral harps today.

Bibliography

- Victor-Charles Mahillon, Catalogue descriptif et analytique du Musée Instrumental du Conservatoire Royal de Musique de Bruxelles, i, Gand, 1893, p. 338-342.

- Laure Barthel, Au cœur de la harpe au XVIIIe siècle, s.l., 2005, p. 58.