August 2024

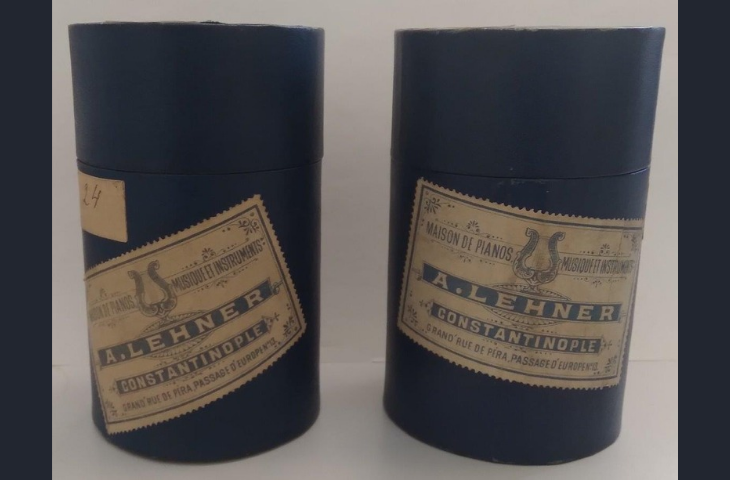

Fig.1

Boxes of phonographic cylinders, in the process of being inventoried

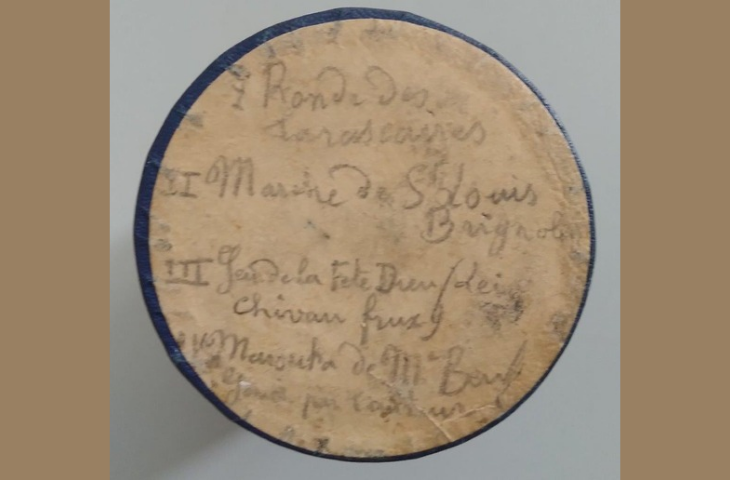

Fig.2

Boxes of phonographic cylinders, in the process of being inventoried

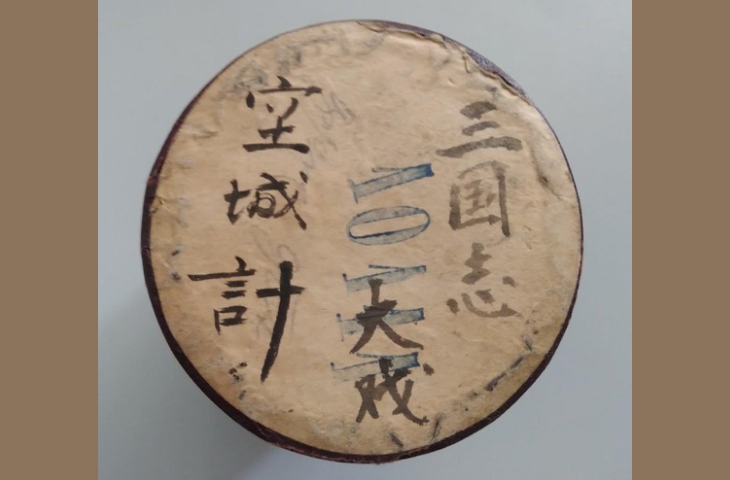

Fig.3

Boxes of phonographic cylinders, in the process of being inventoried

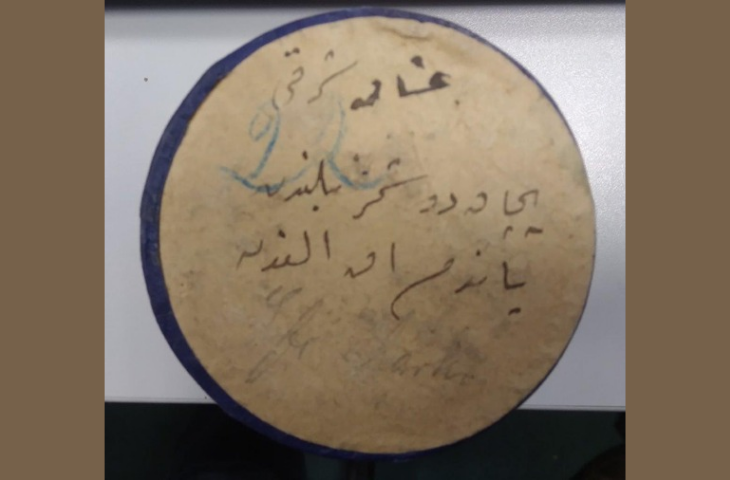

Fig.4

Boxes of phonographic cylinders, in the process of being inventoried

Fig.5

Boxes of phonographic cylinders, in the process of being inventoried

A worldwide sound collection from 1900 onwards

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, probably towards the very end of 1899, Victor-Charles Mahillon, curator of the Instrumental Museum of the Royal Conservatoire in Brussels, conceived the project of building up a ‘collection of graphophone cylinders reproducing popular music from different countries’ (Archives MIM, Correspondance Mahillon). From January 1900 onwards, he established many contacts around the world in order to obtain phonograph recordings: in Brittany (Quimper and then Vannes), London, Istanbul, Madrid, Dublin, Java, Tokyo, Peking, Calcutta, and so on.

The creation of a collection of sound recordings dedicated to the world's popular musical traditions is striking in its precociousness. It is exactly at the same time as the Phonogrammarchiv project initiated by the Academy of Sciences in Vienna and the Musée phonographique designed by Léon Azoulay for the Société anthropologique de Paris.

However, while the latter two projects integrated instrumental music into a vast programme with mainly ethnographic and linguistic aims, Mahillon's project gave it a central role, with the declared aim of using the phonograph as a tool for musicological and organological documentation. In this respect, it predates by several years the famous Phonogramm-Archiv created at the Berlin Institute of Psychology by Carl Stumpf and Erich Moritz von Hornbostel.

A long-overlooked collection

Unlike the renowned phonographic archives in Vienna, Paris and Berlin, the Brussels archives remained unknown until recently, probably because, as part of a museum of musical instruments, they were never identified as such and therefore never systematically inventoried.

The exact extent and composition of the collection is therefore unknown, but the inclusion in the 1942 inventory of ‘forty-eight graphophone cylinders recording exotic music’ (inv. 3590) in a review of unexhibited items suggests that it never developed to the same extent as the other collections.

A partial yet valuable rediscovery

Despite these gaps, the rediscovery in the MIM reserves of forty-three wax phonograph cylinders, mostly preserved in their original boxes, has made it possible to reconstitute part of this forgotten collection. Alongside a continuous numbering system (1 to 43), which may be the result of the 1942 inspection, there are a number of inscriptions which, in the case of the numbers, testify to the existence of several older sub-collections that are now incomplete and, in the case of the texts, attest to a wide variety of origins: Provence, Egypt, China, India, the Ottoman Empire, England, North America, etc.

Reflecting the acquisition process put in place by the curator, these cylinders are most often devoid of trade marks, but some of them come from companies such as Edison Bell or Columbia, or from local distributors such as Lehner in Istanbul or Bevans & Co in Calcutta. While it is not possible here to give an exhaustive inventory of this collection - which is still in the process of being drawn up - and which has yet to result in the digitisation of the cylinders, a handful of records suffice to demonstrate the immense interest of the Brussels phonographic collection: galoubet, music from popular and religious festivals in Provence, Ottoman repertoire and rebetiko from Istanbul, Peking opera and Chinese popular songs, classical music from Egypt, etc.

Text: Fañch Thoraval

Read the full article