March 2025

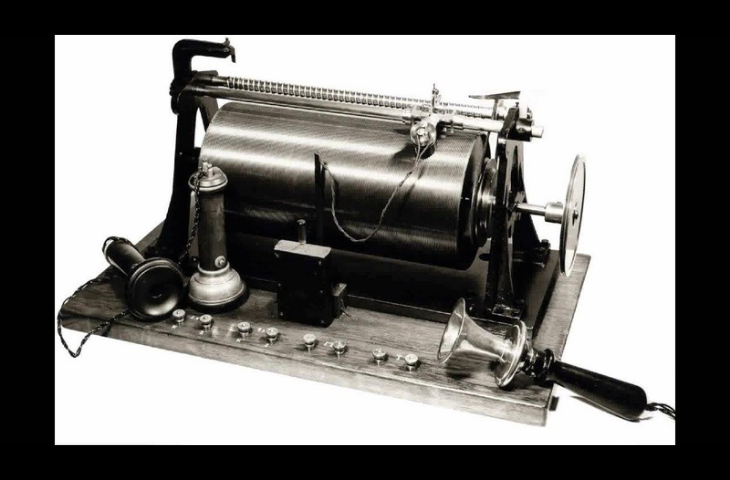

Fig.1

The Poulsen’s Telegraphon, 1898 ©Wikipedia

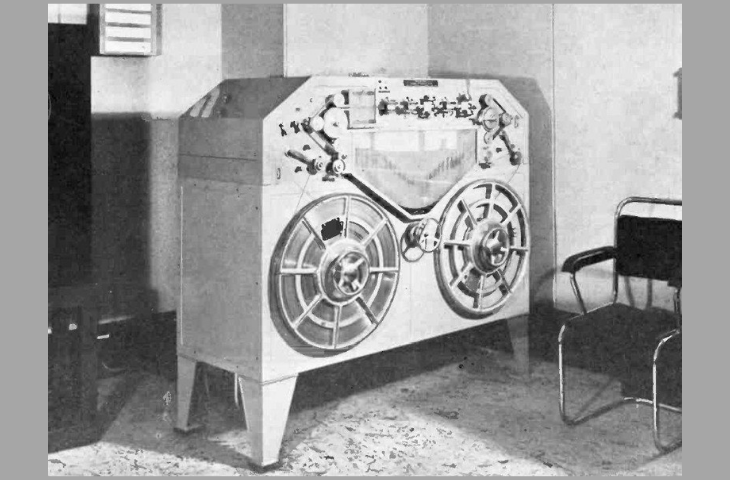

Fig.2

The BBC’s Blattnerphone, 1937, ©Wikimedia

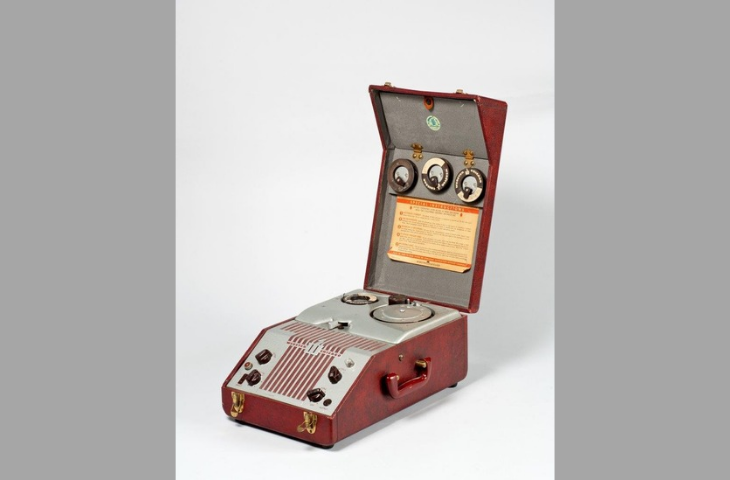

Fig.3

Webster Chicago model 80-1, United States, around 1948, inv.1999.020

Fig.4

Picture from the movie 'The Wire Recorder' by Techmoan

The wire recorder is the oldest magnetic recording system. The American engineer Oberlin Smith conceived the principle theoretically in 1888, but it was the Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen who made the first operational machine, the "Telegraphon", in 1898, using a piano wire wound on a cylinder (Fig.1).

Electromagnetic recording consists of converting the electrical signal of a sound wave into a magnetic signal, and then "etching" this signal with an electromagnet onto a steel wire. By running the wire past the electromagnet connected to the microphone, the variations in the magnetic field, and therefore in the sound, are recorded. To listen to the recorded sound, the steel wire must be passed in front of the electromagnet again.

In contrast to disc recording, there is no physical contact between the recorder and the media. This means that there is no wear and tear and the sound quality is "theoretically" better. However, as we do not yet know how to amplify the electrical signal, the sound of the device is much too weak to be used for music. It was used as a dictaphone and telephone answering machine. The German Navy also used it to send coded messages during the First World War. The wire had the undeniable advantage of offering a much longer recording time than cylinders (3 min) or 78 rpm records (5 min).

With the advent of amplifiers in the 1920s, wire recording regained importance despite the heavy and cumbersome equipment. In the 1930s, German and British radio stations used tape recorders that operated with 3 mm wide steel tapes. A single 45-minute reel was 60 cm in diameter and weighed almost 20 kg (Fig.2)! It is also an object to be used with care. Considering that the steel tape rotates at a speed of 1.5 metres per second, it is like working with a circular saw! The BBC engineers handle their machine from inside a cage, to avoid having their fingers cut by unruly pieces of metal. And while technically the assembly from the wire is feasible, in practice it was more complicated, requiring a blowtorch and welding equipment...

Thanks to technical improvements in the holder, just after the WWII the result is a magnetic wire made of chrome steel, as thin as a human hair. This made it possible to considerably reduce the size of tape recorders and even to produce portable models, as in the case of the Webster Chicago model 80-1 presented at the MIM (Fig.3).

Webster Chicago Corporation is an electronics company based in Chicago, Illinois. Many products are sold under the Webcor brand name, such as wire reels that can be stored in the cover with the microphone and connecting cables. The firm simplified the design of the wire recorder and developed a device that sold for only $150, half the price of competing models. In the 1950s, it was the first manufacturer of wire recorders in the United States.

In practice, a spool of wire is placed at the top left of the device and connected to the large spool on the right, taking care to pass it through the playback (or recording) head which is located between the two. This is attached to a mechanism that slowly moves it up and down during playback to ensure that the spools are well aligned, like a fishing rod reel. Because if knots were to occur, it would be almost impossible to untangle them (Fig.4). If the space is small, it will not be heard because of the speed of 60 cm per second. Thanks to the thinness of the wire, up to an hour's worth of music can be recorded and played, which is a length of wire of over 2 km!

Despite being used until the 1960s, wire was not widely used. The brief heyday of wire recording lasted from 1946 to 1954. Wire recording was replaced by plastic magnetic tape recording, which was thinner than wire and could therefore record even longer, and which also had undeniable qualities in terms of musical recording.

Text: Matthieu Thonon