Acquisition of a kemangeh roumy

When in 1878, Victor Mahillon (1841–1924), newly appointed as the first curator of the Musée des instruments du Conservatoire in Brussels, inventoried the nearly 300 instruments then constituting the collection of the new museum, he categorized this instrument as a German viola d’amore.[1] From a purely formal view this was not an illogical decision. Its morphology is that of a viola d’amore, a bowed chordophone with sympathetic strings, enjoying a certain success in the eighteenth century, especially in the German-speaking countries and in Italy. However, we now know that the instrument inv...

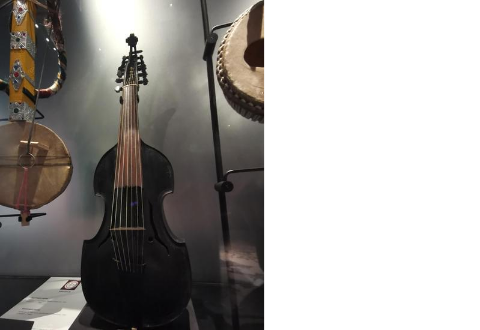

When in 1878, Victor Mahillon (1841–1924), newly appointed as the first curator of the Musée des instruments du Conservatoire in Brussels, inventoried the nearly 300 instruments then constituting the collection of the new museum, he categorized this instrument as a German viola d’amore.[1] From a purely formal view this was not an illogical decision. Its morphology is that of a viola d’amore, a bowed chordophone with sympathetic strings, enjoying a certain success in the eighteenth century, especially in the German-speaking countries and in Italy. However, we now know that the instrument inv. no. 0225 came from Egypt.

In 1839, at the request of the musicographer François-Joseph Fétis (1784-1871), director of the Brussels Conservatory and Kapellmeister to Leopold I, the Belgian government acquired a collection of sixteen Arabic instruments from Étienne Zizinia (or Stephanos Tsitsinias, 1794-1868), a wealthy Greek shipping magnate, naturalized French, newly appointed Belgian consul in Alexandria.[3] A major port of the Ottoman Empire linking the Maghreb to the Levant and southern Europe - the only one capable of receiving large ships in the Mediterranean - Alexandria was then a cosmopolitan melting pot where populations from North Africa, the Middle East and the Mediterranean met, embracing Turks, Maghribs, Greeks, Syrians, Albanians and Jews.[4]

[1] See Victor-Charles Mahillon, Catalogue descriptif & analytique du Musée instrumental du Conservatoire royal de musique de Bruxelles, vol. 1 (Ghent: Ad. Hoste, 1893), 322.

[2] See François-Joseph Fétis, Histoire générale de la musique depuis les temps les plus anciens jusqu’à nos jours (Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot frères, fils et Cie, 1869), vol. 2, 37n.

[3] See François-Joseph Fétis, Histoire générale de la musique depuis les temps les plus anciens jusqu’à nos jours (Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot frères, fils et Cie, 1869), vol. 2, 37n.

[4] See Michael J. Reimer, ‘Ottoman Alexandria: The Paradox of Decline and the Reconfiguration of Power in Eighteenth-Century Arab Provinces’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 37/2 (1994): 107, 114.

Eurocentrism

It is not without significance that Fétis undertook to acquire Egyptian instruments at the very moment when, forced into neutrality by the Treaty of London in April 1839, the young Belgian kingdom became involved in the 'Oriental Question' and the complex power games between France, England, the Ottoman Empire and the Egyptian Viceroyalty. While the conflict between the Egypt of the Khedive Muhammed Ali and his ‘theoretical’ sovereign, Sultan Mahmud II, was entering a new episode with the second Egyptian-Ottoman war (1839-1840), and while France and England were taking advantage of the...

It is not without significance that Fétis undertook to acquire Egyptian instruments at the very moment when, forced into neutrality by the Treaty of London in April 1839, the young Belgian kingdom became involved in the 'Oriental Question' and the complex power games between France, England, the Ottoman Empire and the Egyptian Viceroyalty. While the conflict between the Egypt of the Khedive Muhammed Ali and his ‘theoretical’ sovereign, Sultan Mahmud II, was entering a new episode with the second Egyptian-Ottoman war (1839-1840), and while France and England were taking advantage of the conflict to assert their respective influences on each of the parties, Belgium prepared its commercial and colonial plans (the latter particularly in Crete and then Abyssinia), trying to ‘navigate’ diplomatically between the Sublime Porte in Istanbul and the Viceroyalty in Alexandria. This resulted, amongst others, in the setting up of consular agents in Alexandria, notably with the unofficial nomination of Edouard Blondeel van Cuelebroeck in 1837, and then the more official one of Etienne Zizinia in November 1839. The latter had been living in Egypt for a long time, spoke Turkish, maintained regular relations with Muhammed Ali, and had a knowledge of local traditions.[1] He was therefore considered a suitable intermediary for the collecting of representative examples of the Egyptian instrumentarium for Fétis.

Fétis was a zealous collector of ‘musical instruments of diverse nations and of all times’.[2] He was convinced that the Egyptian collection of musical instruments compiled by Zizinia, ‘in accordance with the note I had provided’, was ‘the most comprehensive collection of this kind in the whole of Europe’.[3] Apart from prestige, Fétis’ ambition was to study the evolution of music, its language and its instruments, in a perspective broad enough to highlight his teleological perception of musical traditions. In 1831 he wrote:

It is no longer enough to make a history of each part or each period of music and to put these pieces in succession, as has been done until now. So many recent discoveries ... show that everything is connected between the music of the Ancients, of the peoples of Asia, of the ancient peoples of Northern Europe and of the modern state. The duty of the historian will be to make people aware of the chain which links all these.[4]

Inspired by an unshakeable faith in progress, he saw non-European instruments as witnesses to earlier stages of an evolution that had culminated in the (supposedly) unrivalled quality of European instruments. He stated in 1769:

Among people of all races and all times, music is primitively only the satisfaction of an instinctive, sentimental or traditional need; it becomes art only as far as the system of its elements is complete, and ... this condition being fulfilled only in the music of modern Europeans, this alone must be considered as art.[5]

Reflecting an obvious sense of superiority, his perceptions and opinions on non-European music were archetypical of their time: Euro- and sociocentric.

[1] See Jan Anckaers, Small Power Diplomacy and Commerce, Center for Ottoman Diplomacy History, Isis, 2013, passim.

[2] Fétis, Histoire, vol. 2, 37 (‘ma collection d’instruments de musique de diverses nations et de toutes les époques’).

[3] Fétis, Histoire, vol. 2, 37n (‘A ma demande, le gouvernement belge a bien voulu charger le consul belge à Alexandrie de faire … acheter pour mon compte la collections complète des instruments de musique arabes, conformément à la note que j’ai fournie … C’est, je crois, la collection la plus complète de cette espèce qui ait été réunie en Europe’).

[4] Fétis, ‘Sur la nécessité d’écrire l’histoire de la musique sur un meilleur plan qu’on ne l’a fait jusqu’ici,’ Revue musicale, June 4, 1831, 140 (‘il ne suffit plus de faire l’histoire de chaque partie ou de chaque époque de la musique et de mettre ces morceaux à la suite l’un de l’autre comme on l’a fait jusqu’ici. Tant de découvertes récentes … démontrent que tout se tient entre la musique des Anciens, des peuples de l’Asie, des anciennes peuplades du Nord de l’Europe et de l’état moderne. Le devoir de l’historien sera de rendre sensible la chaîne qui lie toutes ces choses’).

[5] Fétis, Histoire, vol. 1, 5 (‘Chez les peuples de toutes les races et de tous les temps, la musique n’est primitivement que la satisfaction d’un besoin instinctif, sentimental ou traditionnel; elle ne devient art qu’autant que le système de ses éléments est complet, et … cette condition n’étant réalisée que dans la musique des Européens modernes, celle-ci seule doit être considérée comme art: elle est le but final de mon livre’).

Kemangeh roumy and viola d'amore

Among the sixteen instruments which Zizinia collected for Fétis in Alexandria - lutes, flutes, oboes, drums, lyres, zithers and viols - was this 'kemangeh roumy'.[1] As said, this instrument exhibits the characteristics of the European viola d'amore: it has seven melodic strings and seven sympathetic strings (i.e. strings that vibrate sympathetically, without being touched by the musician). The sympathetic strings run under the fingerboard, which has no frets. The system of attachment of the melodic and sympathetic strings is very similar to that of the European viola d’amore. The sound holes...

Among the sixteen instruments which Zizinia collected for Fétis in Alexandria - lutes, flutes, oboes, drums, lyres, zithers and viols - was this 'kemangeh roumy'.[1] As said, this instrument exhibits the characteristics of the European viola d'amore: it has seven melodic strings and seven sympathetic strings (i.e. strings that vibrate sympathetically, without being touched by the musician). The sympathetic strings run under the fingerboard, which has no frets. The system of attachment of the melodic and sympathetic strings is very similar to that of the European viola d’amore. The sound holes are in the shape of flames, a common characteristic on viole d'amore. The black varnish covering the instrument is a recurrent feature of bowed instruments built in Austria in the second half of the eighteenth century[2].

[1] See also the 1872 manuscript catalogue of Fétis’ collection, compiled after his death by his son Édouard and preserved at the MIM archive: ‘nr. 7. viole d’amour noire’.

[2] Michel Lorge, ‘Her dark materials’, The Strad, March 2022, p. 70-71.

Tuning

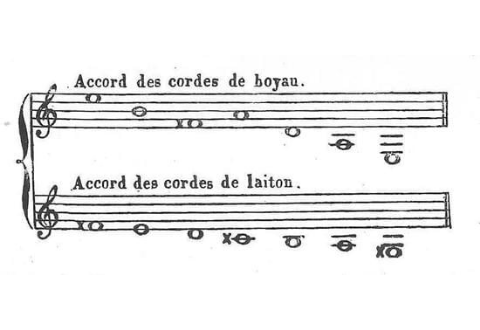

According to Fétis, one particularity that distinguishes the kemangeh roumy from the European viola d'amore is its tuning. The tuning is reversed in comparison with western bowed instruments, where the lowest strings are on the left side and the highest on the right. Fétis associates this characteristic with the shape of the tailpiece, which is longer on the left than on the right.[1] On European violas d'amore the tailpiece is either symmetrical or longer on the right side.

[1] Fétis, Histoire, vol. 2, 141.

Internal structure

The internal structure of the instrument strongly suggests that it was designed for a European-style tuning, with the lower strings on the left, as the bass bar, carved in the wood of the inner side of the sound board, is located under the left foot of the bridge rather than under the right foot. The general impression from an internal examination is that the kemangeh roumy was made by a European or a violin maker trained in European techniques. For example, the sound holes are chamfered from the inside, a typical feature of European Baroque violin making. The presence of linings and corner...

The internal structure of the instrument strongly suggests that it was designed for a European-style tuning, with the lower strings on the left, as the bass bar, carved in the wood of the inner side of the sound board, is located under the left foot of the bridge rather than under the right foot. The general impression from an internal examination is that the kemangeh roumy was made by a European or a violin maker trained in European techniques. For example, the sound holes are chamfered from the inside, a typical feature of European Baroque violin making. The presence of linings and corner blocks suggests that the instrument was built on a mould, like Cremonese violins. For these reasons, the kemangeh roumy does not fit well into Zizinia's ‘Arab’ collection, and one wonders why Fétis added it to his wish list.

Fétis and Villoteau

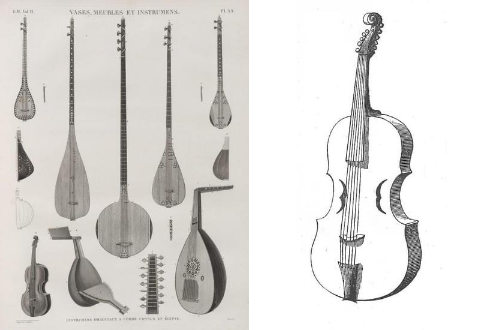

It should be noted that 40 years before Fétis, Guillaume André Villoteau (1759–1839), one of the savants who joined Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign (1799–1801), had depicted a similar kemangeh roumy in his contribution on musical instruments to the famous Description de l’Égypte, on a plate with engravings entitled: ‘Oriental instruments known in Egypt’.

Villoteau’s report on the kemangeh roumy reads that ‘this viol bears a strong resemblance to the instrument known, not long ago, in France and Italy, under the name of viola d’amore’.[1] According to Villoteau, kemangeh literally means ‘place...

It should be noted that 40 years before Fétis, Guillaume André Villoteau (1759–1839), one of the savants who joined Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign (1799–1801), had depicted a similar kemangeh roumy in his contribution on musical instruments to the famous Description de l’Égypte, on a plate with engravings entitled: ‘Oriental instruments known in Egypt’.

Villoteau’s report on the kemangeh roumy reads that ‘this viol bears a strong resemblance to the instrument known, not long ago, in France and Italy, under the name of viola d’amore’.[1] According to Villoteau, kemangeh literally means ‘place of the bow’ (‘keman’ = ‘bow, and ‘geh’ = ‘place), in other words ‘bowed instrument’. ‘Roumy’, he says, refers to ‘grec’ (‘Greek’).[2] Thus, the kemangeh roumy is a ‘Greek viol’. In Egypt, Villoteau saw kemangeh roumys of different sizes. The one he depicts is rather small, with six ‘mobile’ (melodic) and six ‘stable’ (sympathetic) strings.[3]

Fétis knew well Villoteau’s publication, which Villoteau referred to in an exchange of letters with Fétis in 1825, and of which Fétis wrote a detailed account a few years later.[4] He probably aspired to possess a similar Egyptian collection, which may explain why he put a kemangeh roumy on the list sent to Zizinia. Copying from Villoteau’s report, Fétis calls the kemangeh roumy a ‘viole grecque’.[5] He describes Villoteau’s kemangeh roumy with twelve strings, but adds: ‘There is another, much larger kemangeh roumy, which is 75 centimeters long and has fourteen strings – it is in my collection’.[6] Curiously, in his Histoire Générale de la musique, Fétis does not show his own kemangeh roumy (which later became part of the MIM), but the instrument in Villoteau’s picture.

[1] Villoteau, ‘Description historique, technique et littéraire des instrumens de musique des Orientaux’, in Edme François Jomard (ed.), Description de l’Egypte … État moderne, vol. 1 (Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1809), 882 (‘Cette viole ressemble beaucoup à l’instrument qu’on connoissoit, il n’y a pas très-long-temps, en France et en Italie, sous le nom de viole d’amour’).

[2] Villoteau, ‘Description’, 881.

[3] See Villoteau, ‘Description’, 882.

[4] Robert Wangermée, François-Joseph Fétis, Correspondance, éd. Robert Wangermée (Sprimont, Mardaga, 2006), 38-41, and Revue musicale 1/1 (1827), nos. 15-16, 370-381, 389-402; 1/2 (1828), nos. 25, 1-9.

[5] Fétis, Histoire, vol. 2, 134.

[6] Fétis, Histoire, vol. 2, 140, 140n (‘Il y a une autre kemângeh roumy, beaucoup plus grande, dont la longueur totale est de 75 centimètres, et qui a quatorze cordes … Elle se trouve dans ma collection’).

Migration

Villoteau’s and Fétis’ testimonies raise the question of whether, perhaps, the European viola d’amore was used by local musicians in late eighteenth-century Egypt. As mentioned above, the kemangeh roumy seems to be nothing but a retuned European viola d’amore. It is known that in de second half of the eighteenth century, viole d’amore was amongst the goods which were traded between Europe and the Ottoman Empire – of which the Viceroyalty Egypt was still a part, despite the Mamluks’ desire for autonomy. The first evidence of viole d’amore being played in Istanbul appeared in the 1760s. In his...

Villoteau’s and Fétis’ testimonies raise the question of whether, perhaps, the European viola d’amore was used by local musicians in late eighteenth-century Egypt. As mentioned above, the kemangeh roumy seems to be nothing but a retuned European viola d’amore. It is known that in de second half of the eighteenth century, viole d’amore was amongst the goods which were traded between Europe and the Ottoman Empire – of which the Viceroyalty Egypt was still a part, despite the Mamluks’ desire for autonomy. The first evidence of viole d’amore being played in Istanbul appeared in the 1760s. In his Mémoire sur les Turcs et les Tartares, Baron de Tott (1733–1793), a French-Slovak diplomat who lived in Istanbul in the 1760s and 1770s, describes a concert given by a Turkish chamber orchestra. This orchestra was set up ‘at the back of the apartment where the musicians, crouching on their heels, play melodious and lively tunes, but always in unisono, without scores’. In addition to a three-stringed viol, a dervish flute (ney), a tanbur (long-necked lute), clarinets, panpipes, and a tambourine, the orchestra includes ‘the viola d’amore, which [the Turkish musicians] have adopted’.[1] In his Letteratura turchesca of 1787, the Italian philosopher Giambattista Toderini (1728–1799) writes about the instruments used by the Turks: Amongst the ‘Musici Stromenti da camera’ is listed the ‘Sinè keman, viola d’amore’.[2] The sine keman (‘breast fiddle’[3]) became one of the favourite instruments at the imperial court in Istanbul, replacing the kemançe spike fiddle of Persian origin.[4]

The Horniman museum in London holds a viola d’amore with a dark brown varnish, similar to the MIM’s kemangeh roumy. It has six melodic and three sympathetic strings.[5] This instrument is obviously of French inspiration, since it bears a label reading ‘Fab.e Chateaureynaud Constantinople’. Chateau-Reynaud seems to have worked as a violin maker in Istanbul from the 1830s onwards.[6]

[1] Baron Ferenc de Tott, Mémoires … sur les Turcs et les Tartares (Amsterdam: s.n., 1784), 112 (‘Un violon à trois cordes, … la viole d’amour, qu’ils ont adopté[e], la flûte de derviche …, le tambour [sic], espèce de mandoline à long manche & à cordes de métal, les chalumeaux, ou la flûte de Pan, & le tambour de basque destiné à rendre la mesure plus sensible, composent cet orchestre. Il s’établit au fond d’un appartement où les musiciens ac[c]roupis sur leurs talons, jouent sans musique écrite, des airs mélodieux ou vifs mais toujours à l’unisson’).

[2] Giambattista Toderini, Letteratura turchesca (Venice: Giacomo Storti, 1787), 236.

[3] See Tureng. The Multilingual Dictionary: ‘sine’ = chest, breast (https://tureng.com/en/turkish-english/sine).

[4] See Martin Greve, Makamsiz: Individualization of Traditional Music on the Eve of Kemalist Turkey (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag, 2017), 175.

[5] See Jonathan Hill, ‘Viola d’amore made in Contantinople / Istanbul, 19th century’(https://www.jonathanhill-luthier.com/viola-damore-made-in-istanbul).

[6] See Coup d’œil général sur l’exposition nationale à Constantinople. Extraits du Journal de Constantinople (October 1, 1863), 119-120.

Another record of the same type of instrument is from the hand of the Turkish musician and musicographer Rauf Yekta Bey (1871–1935) writing in the early 1920s that the sine keman was still

the most popular instrument among Turkish classical music lovers … The chamber music of the Turks being very soft, the viola d’amore’s strangely poetic and melancholic timbre suits it better … and its particular charm is enjoyed more fully in the luxurious and mysterious surroundings of the Oriental salons.[1]

Yekta says that he owns a sine keman whose label reads ‘Mathias Thir fecit / Viennae, Anno...

Another record of the same type of instrument is from the hand of the Turkish musician and musicographer Rauf Yekta Bey (1871–1935) writing in the early 1920s that the sine keman was still

the most popular instrument among Turkish classical music lovers … The chamber music of the Turks being very soft, the viola d’amore’s strangely poetic and melancholic timbre suits it better … and its particular charm is enjoyed more fully in the luxurious and mysterious surroundings of the Oriental salons.[1]

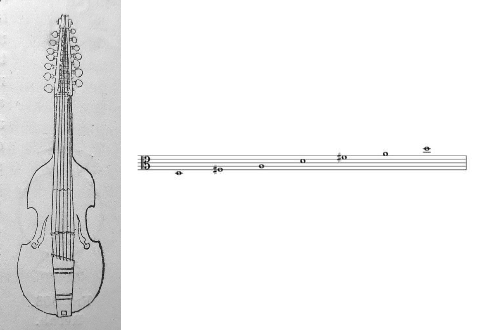

Yekta says that he owns a sine keman whose label reads ‘Mathias Thir fecit / Viennae, Anno 1795’.[2] He also gives the tuning of the instrument and provides an illustration. Contrary to the tuning given by Fétis, this one is in line with European practice. The tailpiece, on the other hand, is reversed, like that of the kemangeh roumy of the MIM.[3] Yekta assumes that the viola d’amore arrived in Istanbul from Austria-Hungary via Wallachia and Serbia, the earliest ones all being made in Vienna.[4] Other authors believe that the viola d’amore had been found its way to Turkish music mainly through the Venice-Istanbul connection.[5]

The sine keman was an aristocratic instrument also appreciated outside the realm of the Ottoman capital. François Charles Hugues Laurent Pouqueville (1770–1838), French diplomat, explorer, and member of Napoleon’s Commission des sciences et des arts in Egypt traveled extensively through Ottoman Greece from 1798 to 1801. At the court of Tripoli (Tripoliçe) in the Peloponnese, Pouqueville attended a concert where music was played on the sine kenam, which, he said, ‘is, strictly speaking, the viola d’amore; it was brought from Italy’.[6] In Egypt, the viola d’amore was called a ‘roumy’ viol or a ‘Greek violin’, to refer to its foreign, non-muslim origin.

[1] Raouf Yekta Bey, ‘La musique turque’, in Lionel de la Laurencie and Albert Lavignac (ed.), Encyclopédie de la musique et dictionnaire du Conservatoire. Première partie. Histoire de la musique, vol. 5 (Paris: Delagrave, 1922), 3014 (‘c’est l’instrument le plus prisé par les amateurs de la musique classique parmi les Turcs … la musique de chambre des Turcs étant très douce, le timbre étrangement poétique et mélancolique de la viole d’amour lui convient mieux … et son charme particulier est mieux savouré dans le cadre luxueux et mystérieux des salons orientaux’).

[2] See Yekta Bey, ‘La musique turque’, 3014.

[3] Since the lowest peg is placed on the left side of the pegbox, as is customary on European stringed instruments, the engraving has probably not been reversed.

[4] See Yekta Bey, ‘La musique turque’, 3014.

[5] See Greve, Makamsiz, 23.

[6] François-Charles-Hugues-Laurent Pouqueville, Voyage en Morée, à Constantinople, en Albanie, et dans plusieurs autres parties de l'Empire Ottoman (Paris: Gabon et compe, 1805), vol. 1, 54 (‘c’est, à proprement dire, la viole d’amour; on les tire d’Italie’).

The kemangeh roumy at the MIM

When Villoteau saw kemangeh roumysin Cairo at the end of the 1790s, he described and depicted one in his report, but considered it not interesting enough to take with him to France. Apart from Villoteau’s illustration and Fétis’ instrument, no other Egyptian kemangeh roumysin the shape of a viola d’amore are known. Consequently, Fétis’ kemangeh roumymay well be the first (and only?) one brought to Europe. It may have been of Austrian production, and may have traveled from Vienna to Alexandria and then to Brussels.

After Fétis’ death in 1871 his sons Édouard and Adolphe sold his musical...

When Villoteau saw kemangeh roumysin Cairo at the end of the 1790s, he described and depicted one in his report, but considered it not interesting enough to take with him to France. Apart from Villoteau’s illustration and Fétis’ instrument, no other Egyptian kemangeh roumysin the shape of a viola d’amore are known. Consequently, Fétis’ kemangeh roumymay well be the first (and only?) one brought to Europe. It may have been of Austrian production, and may have traveled from Vienna to Alexandria and then to Brussels.

After Fétis’ death in 1871 his sons Édouard and Adolphe sold his musical instruments to the Belgian State. In 1873 they were accommodated in the library of the Conservatoire royal de musique. In 1877, the collection, including the kemangeh roumy, became part of the Conservatoire’s new Musée instrumental.